Early Detection is Key: Controlling Invasive Plants in Your Garden

February in Chicagoland may seem quiet in the garden, but it's actually a crucial time to combat invasive plants. Three particularly troublesome invaders to focus on right now are buckthorn, barberry and lesser celandine. These aggressive plants can quickly take over your garden, choking out native species and disrupting the local ecosystem. But with a little knowledge and effort, you can gain the upper hand.

Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

Above Right: Bulbets and tubers of Lesser Celandine. Above Center and Left: Native plants like Virigina Bluebells and Golden Ragwort are perfect to replace Lesser celandine once removed.

Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) Dog surrounded by invasive Barberry

Dog surrounded by invasive Barberry

Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

EcoFun Fact: A Tale of Two Invaders: How Barberry and Buckthorn Arrived in the U.S.

It's fascinating how seemingly harmless plants can become invasive threats. Both barberry and buckthorn have unique histories of how they arrived in the United States, highlighting how human actions can have unintended consequences for the environment.

Barberry's Ornamental Appeal:

European settlers brought barberry (Berberis thunbergii) to North America in the 1800s, primarily for its ornamental value. The shrub's attractive foliage, hardiness, and tolerance to various conditions made it a popular choice for gardens and hedges. However, its ability to spread rapidly through birds and other wildlife dispersing its seeds allowed it to escape cultivation and invade natural areas.

Buckthorn's Hedgerow History:

Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) also arrived from Europe in the 1800s, but for a different purpose: hedgerows. Its dense growth habit and thorny branches made it ideal for creating living fences to contain livestock and delineate property lines. Unfortunately, buckthorn's prolific seed production and adaptability allowed it to spread quickly beyond its intended use, invading forests and fields.

The Unforeseen Consequences:

In both cases, the introduction of these non-native plants had unintended and detrimental effects on native ecosystems. They outcompete native species, alter soil conditions, and disrupt natural processes, leading to a decline in biodiversity and ecological health.

Understanding the history of how these invasive plants arrived in the U.S. underscores the importance of careful plant selection and the potential consequences of introducing non-native species. By choosing native plants and managing invasive species, we can help protect and restore the balance of our natural environment.

Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)

Lesser Celandine (Ficaria verna)- The Problem: This small plant with bright yellow flowers emerges earlier than most native spring ephemerals. In February, you might spot its kidney-shaped leaves starting to peek through the soil. This aggressive plant forms dense mats that smother native wildflowers and prevent them from accessing sunlight and nutrients. It thrives in a variety of conditions, making it a formidable opponent. It spreads rapidly in two ways: through bulblets and tubers.

- What to Do:

- Inspect: Scan for low-growing clumps and tiny green leaves.

- Remove: Hand-pull small patches, ensuring you get the entire root system.

- Smother: Cover larger patches with cardboard or mulch.

- Organic Herbicide: Consider a pre-burn technique (lightly flame leaves) followed by an OMRI-approved organic herbicide.

- Replant: Once clear, establish dense plantings of competitive native species like Virginia Bluebells or Golden Ragwort.

Above Right: Bulbets and tubers of Lesser Celandine. Above Center and Left: Native plants like Virigina Bluebells and Golden Ragwort are perfect to replace Lesser celandine once removed.

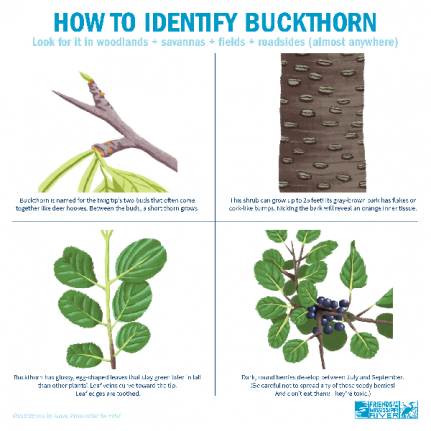

Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica)

- The Problem: Buckthorn is a woody invasive that was brought over by Europeans as a popular hedge plant. It quickly takes over areas, as it leaves out extremely early and retains leaves late into the fall, depriving native plants of essential sunlight and resources. Its dense growth also alters soil conditions, hindering native plant survival. It's easy to spot in winter by its dark bark, thorns, and lingering black berries.

- What to Do:

- Identify: Look for smooth gray-brown bark, thorns, and tall stems with tightly spaced buds.

- Remove: Prune or cut young saplings (remove the entire root). For larger plants, plan for stump treatments with herbicide in late winter/early spring.

Dog surrounded by invasive Barberry

Dog surrounded by invasive BarberryBarberry (Berberis thunbergii)

- The Problem: This popular shrub, which was also used in the past as a hedge plant, forms dense thickets, crowding out native plants, altering soil pH, and providing habitat for ticks.

- What to Do:

- Remove: Dig out small plants (remove the entire root). For larger shrubs and thickets, use the cut-stump method with herbicide.

- Replace: Choose native alternatives like Ninebark, Winterberry, or Virginia Sweet Spire. If you are trying to use Barberry as a hedge, consider Prickly Pear and Wild Roses, which have sharp thorns and can form a thicket.

Working Together for Resilient Gardens

Winter is the perfect time for observation and planning. By taking proactive steps now, you can prevent these invasive species from taking over your garden and support a healthy, thriving ecosystem. Need help? Don't hesitate to reach out for a winter garden consultation!_______________________________________________________

EcoFun Fact: A Tale of Two Invaders: How Barberry and Buckthorn Arrived in the U.S.

It's fascinating how seemingly harmless plants can become invasive threats. Both barberry and buckthorn have unique histories of how they arrived in the United States, highlighting how human actions can have unintended consequences for the environment.

Barberry's Ornamental Appeal:

European settlers brought barberry (Berberis thunbergii) to North America in the 1800s, primarily for its ornamental value. The shrub's attractive foliage, hardiness, and tolerance to various conditions made it a popular choice for gardens and hedges. However, its ability to spread rapidly through birds and other wildlife dispersing its seeds allowed it to escape cultivation and invade natural areas.

Buckthorn's Hedgerow History:

Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) also arrived from Europe in the 1800s, but for a different purpose: hedgerows. Its dense growth habit and thorny branches made it ideal for creating living fences to contain livestock and delineate property lines. Unfortunately, buckthorn's prolific seed production and adaptability allowed it to spread quickly beyond its intended use, invading forests and fields.

The Unforeseen Consequences:

In both cases, the introduction of these non-native plants had unintended and detrimental effects on native ecosystems. They outcompete native species, alter soil conditions, and disrupt natural processes, leading to a decline in biodiversity and ecological health.

Understanding the history of how these invasive plants arrived in the U.S. underscores the importance of careful plant selection and the potential consequences of introducing non-native species. By choosing native plants and managing invasive species, we can help protect and restore the balance of our natural environment.